"Court admissibility hearings are 'not the appropriate time to begin the process of peer review of the data.'"

A United States federal jury convicted 35-year-old Roman Sterlingov of money laundering and operating an unlicensed money transmission business, finding that he operated a Bitcoin mixing service called Bitcoin Fog (such early custodial mixing services pooled Bitcoin from many users, obfuscating ownership upon withdrawal and thereby providing privacy on the publicly viewable blockchain). Sterlingov, a Russian-Swedish citizen with no ties to the U.S., admitted to using Bitcoin Fog to keep his Bitcoin transactions private, which the district court judge acknowledged remains legal. But Sterlingov staunchly denied being the operator.

The only evidence linking Sterlingov to the mixing operation was a blockchain tracing report created by closed-source, proprietary software from the private company Chainalysis. According to Professor J.W. Verret, an expert who testified for Sterlingov, Chainalysis’s report:

focused on a Bitcoin transaction from Sterlingov’s Mt. Gox account that traveled to a Bitcoin wallet. We don’t know who owned that wallet or held its private key. From there, a series of transactions were eventually linked to the purchase of a Bitcoin Fog clearnet site that described how to find Bitcoin Fog on the darknet.

Sterlingov may have sold Bitcoin to someone who bought the Bitcoin Fog website, or that someone may have later sold Bitcoin to someone who then sold it to someone else — and so forth — who eventually purchased the domain.

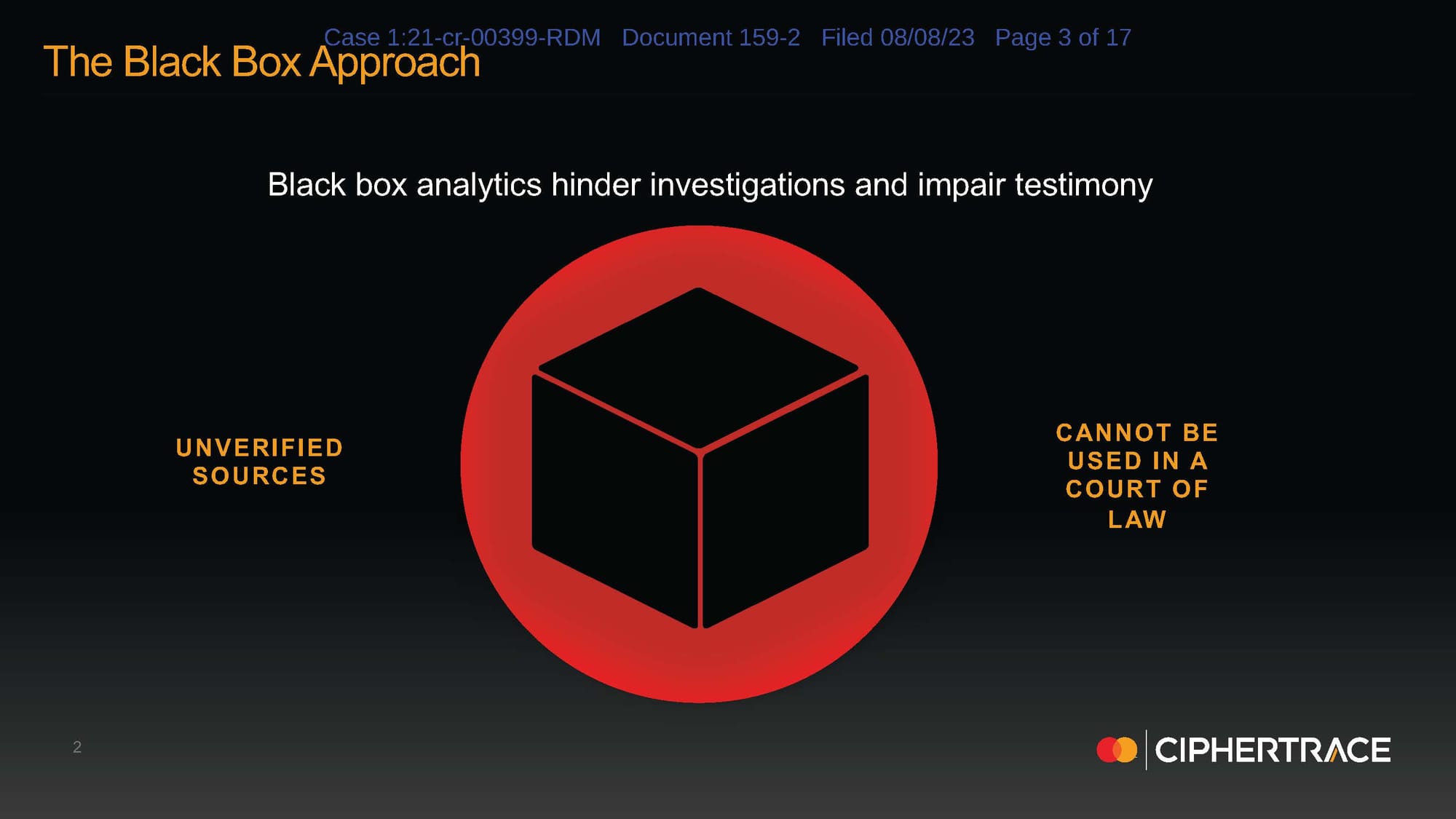

In other words, there is no clear path through the blockchain between Sterlingov’s initially-identified Bitcoin address and the Bitcoin address that purchased the Bitcoin Fog domain. Instead, Chainalysis’s black-box software, Reactor, assigned a probability to Sterlingov’s ownership of the Bitcoin Fog address, based on a number of heuristics (i.e., assumptions) and user inputs.

Sterlingov’s defense team vigorously challenged the admissibility of this blockchain forensic evidence, arguing it failed to meet the scientific rigor demanded of expert evidence in Federal court. Sterlingov sought to view the Reactor source code so the software’s reliability could be verified because, as Chainalysis and the U.S. Government admitted, Reactor had no known error rates, nor had the software been peer-reviewed for accuracy. The district court, however, denied Sterlingov and his experts access to Reactor’s source code, severely hamstringing Sterlingov’s ability to contest the software.

Ultimately, the district court denied Sterlingov’s motion to exclude the Chainalysis Reactor report, ruling that the closed-source software was reliable, despite the fact that it had never been subjected to peer review and there were no known error rates.

After Sterlingov’s conviction, Federal law enforcement touted the infallibility of blockchain forensics, and the skill of its investigators in using these novel techniques:

IRS Criminal Investigation special agents are specially equipped to follow the complex financial trail left by criminals, and we are dedicated to holding those accountable for crimes committed.

…

While the identity of a BTC address owner is generally anonymous (unless the owner opts to make the information publicly available), the evidence at trial demonstrated that law enforcement can identify the owner of a particular bitcoin address by analyzing the blockchain. The analysis can also reveal additional addresses controlled by the same individual or entity.

But if, as Sterlingov’s experts maintained, it is just as likely that someone Sterlingov transacted with, at some point, or someone downstream from that transaction, was the actual Bitcoin Fog operator, the implications for the American public are profound. Anyone who transacts with Bitcoin, or another cryptocurrency, could be fingered as a money launderer. As the number of American households holding and transacting in Bitcoin grows, so too does the pool of potential law enforcement targets. In 2021, 16% of Americans had invested in, used, or traded cryptocurrency, according to a Pew Research poll. In 2022, an NBCNews poll found that number had increased to 20%. And in 2023, one report found that cryptocurrency ownership rates had accelerated to 30% of the American populace. That number implies over 100 million American residents are at risk of prosecution based on unverified, black-box, blockchain analytics (and that’s not counting the millions of non-U.S. residents at risk of prosecution – recall, Sterlingov did not reside in the U.S. nor was he a U.S. citizen).

Bitcoin and blockchain forensics may be on the cutting edge, but Sterlingov’s case is merely the latest chapter in a long history of convictions based on novel (and dubious) forensic techniques (remember bite-mark profiling?). In fact, in many ways, the rise of blockchain forensics today bears striking resemblance to the development and use of the first DNA profiling techniques of the late 1980s and early 1990s, where the justice system’s uncritical adoption outpaced scientific consensus on reliability.

In 1985, a scientist in the U.K. stumbled upon the discovery that the human genome contains variations and patterns that are unique to each individual. Initial use cases included paternity and criminal investigations. By 1987 there were two major for-profit companies performing DNA profiling and paternity testing: Cellmark Diagnostics USA, a subsidiary of Imperial Chemical Industries, the largest chemical company in the U.K., and Lifecodes.

As Robert J. Norris detailed in his book, Exonerated: A History of the Innocence Movement, both companies advertised aggressively to legal and criminal justice professionals. Cellmark claimed its DNA testing could make “the difference between conviction and acquittal.” Lifecodes advertised its testing as “exquisitely accurate,” valid, and reliable – without ever having those tests vetted in court.

Cellmark even hired the chief of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms’ forensics laboratory to ensure its tests would clear the various evidentiary hurdles for introduction in court.

Thus, because “both Cellmark and Lifecodes had multinational parent corporations that were willing to spend billions of dollars each year to spread the use of DNA profiling as much as possible,” the prevailing wisdom was “that the tests utilized would either produce the correct answer or no answer at all – with no real possibility of a false positive.” (Norris) The result was that by 1989, DNA profiling test results had been admitted in over 100 trials (and most likely used to secure many more confessions).

The inflection point came when two New York defense attorneys, Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld (who later founded the Innocence Project, a movement and non-profit that uses DNA evidence, among other techniques, to exonerate the wrongfully convicted), set out to challenge Cellmark and Lifecodes’ techniques in court. The pair saw that the “key issue was that the testing was carried out by private commercial companies” – Lifecodes and Cellmark – and was essentially a “‘black box’, where samples went in and results were spit out, which basically meant convictions were ensured, given the claims of certainty and reliability made by the companies.” (Norris) The first court challenges to the companies’ techniques had focused on the lack of peer review, but were ultimately unsuccessful because of the defense experts’ unfamiliarity with the novel forensic techniques, due in large part, of course, to the techniques’ proprietary nature.

Soon, however, scientists within the field of human genomics grew concerned about what they viewed as sloppy procedures used by Lifecodes and Cellmark (Lifecodes’ CEO, a prolific expert for the prosecution, admitted in a presentation “he would sometimes call a match even when the patterns did not quite line up but were similar,” and that he didn’t “always use proper control tests but knew from experience that the samples matched”). (Norris) Scheck and Neufeld hired a number of these concerned scientists as experts in the defense of Joseph Castro, who was standing trial for murder in New York based on DNA evidence produced by Lifecodes. Remarkably, all but one of the ten experts in the case, both defense and prosecution, issued a joint report agreeing that court admissibility hearings are “not the appropriate time to begin the process of peer review of the data,” and expressing their concerns with Lifecodes’ testing. (Lifecodes’s CEO was, predictably, the only expert not to sign on to the report.) (Norris)

Because of the experts’ consensus, the judge in the Castro case ruled that DNA fingerprinting was generally acceptable and admissible, but Lifecodes’ techniques were not reliable. “The theory underlying forensic DNA typing was accepted, and there were techniques that were accepted to produce reliable results; in this particular case, however, Lifecodes failed to perform all of the necessary tests, and the evidence was thus inadmissible.” (Norris)

The Castro case shattered the public perception that DNA forensics were infallible. Media began reporting more skeptically on DNA evidence and testing (Scheck and Neufeld went on to join the defense team of one Orenthal J. Simpson, securing acquittal in the face of DNA evidence).

The forces that resulted in DNA profiling’s rapid adoption and unquestioning acceptance are at play today with blockchain analytics:

The more convictions obtained as a result of law enforcement agencies’ use of blockchain analytics, the more subscriptions Chainalysis and their competitors can sell. And the federal investigators and prosecutors who make their names securing convictions with private blockchain forensic software, ensuring the federal funds continue to flow to these private companies, are rewarded with well-paying positions within these private companies. For example, one of the lead investigators in Sterlingov’s case went on to become VP of Global Intelligence and Investigations at Binance (presumably he was not part of the investigation that led to Binance’s $4 billion fine for violations of Anti-Money Laundering laws).

And like those first for-profit DNA profiling companies, blockchain analytics companies like Chainalysis are very well-capitalized (having received hundreds of millions of dollars from venture capital and incumbent financial behemoths like Mastercard), and are incentivized to perpetuate the perception that their black-box software will “either produce the correct answer or no answer at all – with no real possibility of a false positive.” (Norris)

Error rates for Chainalysis’s Reactor software are admittedly unknown, and it is not in Chainalysis’s (or its backers’) interest to discover them. This concerning fact did not seem to weigh heavily in the district court’s analysis of reliability in the Sterlingov case. Despite Chainalysis’s expert’s admission that no known error rates for Reactor exist, the district court ruled that the software was nonetheless reliable because the prosecution’s experts testified that, in their anecdotal experience, the software didn’t create false positives, and they were able to replicate the Reactor results in this case with competing products.

But error rates are not just a pedantic scientific technicality: The United States Supreme Court has expressly held that the existence of known error rates is a significant factor that courts must consider when determining whether to admit expert testimony based on forensic evidence. In Daubert v. Merrell-Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc. the Supreme Court instructed courts to examine:

And, the executive branch itself (the branch constitutionally obligated for the prosecution of federal criminal laws) has emphasized the importance of error rates and peer review when determining the reliability of new forensic techniques. In 2016, the President’s Counsel of Advisors on Science and Technology issued an influential report on forensic evidence, recommending that, in addition to the Daubert factors outlined above, courts also consider the existence and maintenance of standards controlling the technique's operation.

This additional factor goes beyond analyzing whether the science behind the forensic technique is sound, and focuses on whether the forensic technique has actually been applied properly. But with black-box forensic software such as Chainalysis’s Reactor, it is impossible to verify that the forensic technique is being applied consistent with industry best practices. For example, at the most basic level, there could be coding errors within the source code itself that cause erroneous results. Indeed, according to one California Law Review article, studies conducted on C++ developers have found that “33% of highly experienced programmers failed to correctly use parentheses when coding basic equations, resulting ‘in almost 1% of all expressions contained in source code being wrong.’”

But it’s not just bugs that could cause software to apply a forensic technique incorrectly. Subjective decisions on how to weight or use certain heuristics are embedded within the source code. This issue came to a head in the Sterlingov case when a defense expert report from Jonelle Still, the Director of Investigations and Intelligence at CipherTrace (a Chainalysis competitor and Mastercard subsidiary), claimed that Chainalysis’s Reactor software was programmed to be overly inclusive in its use of the “behavioral clustering heuristic.” According to Still, CipherTrace does not use behavioral clustering in the way Chainalysis does because it is “not a true representation of the flow of funds on chain.” (In a strange turn of events, after Still issued her expert report, CipherTrace disavowed it based on vague and purportedly privileged “data issues”, forcing the defense to withdraw Ms. Still as a defense expert.)

As Coinbase (which also competes with Chainalysis by selling its Coinbase Analytics blockchain forensics software to the Department of Homeland Security) described blockchain analytics in a blog post: “Unless you own an address yourself, it is very difficult to say with absolute certainty who an address is owned by. This is why it’s more fitting to consider blockchain analytics more of an art than science.”

In other words, without the source-code to examine, it is impossible to tell what artistic licenses have been taken by Chainalysis’s software.

As the disagreement between CipherTrace and Chainalysis’s use of the behavioral clustering heuristic demonstrates, the field of blockchain analytics has yet to develop consensus on best-practices. This lack of scientific consensus and peer review has created a vacuum that is easily filled by public relations and marketing. Like the first DNA forensics techniques, blockchain analytics have obtained an air of infallibility and deterministic certainty before having been seriously tested in court or by the scientific community at large. Indeed, Roman Sterlingov is the first defendant to brave the “trial penalty” and insist on forcing the federal government to prove the reliability of blockchain forensics.

And the proprietary licensing for blockchain forensic software, like the proprietary nature of Cellmark and Lifecodes’ DNA tests, means that defense experts are at a severe disadvantage in their ability to challenge these perceptions of infallibility. That’s why Chainalysis’s CEO is simply incorrect when he claims that the district court’s ruling in the Sterlingov case is the “next best thing to a traditional peer review.” As the DNA forensics experts in the Castro case concluded 35 years ago: court admissibility hearings are “not the appropriate time to begin the process of peer review of the data.” Without robust peer review of Chanalysis’ techniques, the reliability of its Reactor software can never be scientifically established. And this peer review must include rigorous examination of the source code.

Depriving individuals of liberty based on anything less is more than unjust – it’s simply immoral.

The arc of history does not bend towards justice on its own. The courts only began to question DNA forensic techniques once the defense bar actively sought to align experts within the field around protocols for reliable and accurate DNA testing. Roman Sterlingov and his team may have been the first to challenge the black-box that surrounds blockchain analytics, but they cannot be the last. Their efforts have paved the way for future challenges, but it falls to the criminal defense bar, Bitcoin and academic communities to work together to establish standards for the reliable use and application of blockchain forensics.