The arrival and ascent of a self-reliant money represents a rhythmic shift back to the ideals of liberty, individual rights, and civic virtue as America advances into the 21st century

Today’s version of the United States has dug itself into a debt problem that has now reached a degree it has not seen since it concluded the Second World War. Like a health concern that starts out minor and progressively drags on, one day something suddenly arises that demands it be taken seriously. So too has this debt illness lurked in the background for decades, until an unexpected catalyst in the COVID-19 pandemic forced a serious turn for the worse. Awareness is now finally catching up to the reality that difficult choices lie ahead. America now stands at a crossroads, idling between a centralized credit-based system in terminal decline and a new peer offering hope, progress, and opportunity.

There is still a large but shrinking camp who stands by the belief that no serious problem exists; or, if acknowledging that one does, pitch a hopeful fallback argument that the systems, policies, and toolkit of the status quo are up to the task of delivering a solution. A sober look at reality provides a dissenting opinion, with decades of policy blunders at every critical step along the path that led here only prolonging the disease’s terminal date, at the likely cost of worsening the eventual outcome. To Americans on the fence looking for clarity and a path forward, this essay’s visit with our history offers a hopeful antidote to the confusion, paralysis, and denial associated with today’s situation.

Facing similar circumstances with an overwhelming debt problem and an elevated level of internal division exactly two hundred and twenty years ago, Thomas Jefferson famously shifted America’s course onto an upward trajectory with its acquisition of the Louisiana Territory. In hindsight, that decision can be recognized as the culmination of a multi-decade struggle between competing intellectual factions led by Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton on the structure of the new nation's economy and its monetary system. Examining America’s present circumstances through the framework of these two founders reveals insights to a best path forward from today's circumstances as it embraces the opportunity ahead.

New technologies and their adoption into American life have always been the ultimate driver of our long-run economic destiny, with the pendulum of its social order swinging from one founder’s extreme to the other over long stretches measured in lifetimes. Just after the credit-based financial system experienced its first full cardiac arrest in 2008, the technological arrival of a public trustless ledger money appeared with Bitcoin’s launch in January 2009. Its arrival and adoption represent a great wave whose swell is still only just beginning to form.

As money, Bitcoin embodies the Jeffersonian ideals of liberty, individual rights, and self-sufficiency. As it has on only a few other occasions in its history, the American identity will again change poles as it adjusts to the adoption of this new technology. Its twenty-one million units are today’s scarce resource opportunity that parallels the 530 million acres of the Louisiana Territory in the nation's infancy. Its adoption provides a working course for the continuation of this country’s pursuit of progress that it initially set out for itself, and future generations, nearly two hundred and fifty years ago.

On April 30, 1803, the U.S. acquired the 530 million acre Louisiana Territory from Napoleon’s France for 80 million Francs, or $15 million at the transaction’s specified exchange rate. The deal was massive, and its timing was perfect. The country stood only one generation removed from its war for independence, and just over a decade away from ratifying its Constitution after the first attempt at forming a government failed. Any semblance of political stability in the new country was only recently achieved and would have appeared delicate at the time. For the young country, Jefferson's decision was formative.

There were some positive developments hinting at stability leading up to the deal, namely two successive peaceful transitions of the Presidency during the 1790s. The first, from George Washington to John Adams, represented the same political faction and went smoothly. The second, from Adams to Thomas Jefferson, crossed party lines. It came hotly contested under the backdrop of a polarized electorate and divided society. At the turn of the 18th century, it is not clear that a positive outlook would have appeared assured to most participants in the new republic at the time. Most Americans today would find the context familiar.

Despite history’s consensus that the U.S. walked away with an all-time bargain in the deal, it could barely afford the price at the time. It did not have the funds to its name, and still carried a heavy debt burden from the Revolutionary War it had fought only one generation prior. It had to cobble together all available credit it could obtain to close the deal, tapping out its lines with an $11.25 million sovereign bond issuance to the major European banks of the day. Yet even after it converted those proceeds into 60 million francs, it was still short on cash needed to close the deal. It had to get creative for the remainder, assuming the responsibility for 20 million francs of debt that the French government owed to private U.S. citizens. That got the deal done. Whatever it took, the Jefferson Administration was going to lift the offer.

Compared to the modern-day debt problem, the example of Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase illustrates the valuable lesson that utilizing debt is not a poor decision under all circumstances. Rather, applying it wisely – on good, well-timed investments and at cautious levels relative to capacity – is most critical for generating positive outcomes over the long term.

Jefferson effectively committed the country for a generation with his decision. It was not until 1823 that it paid off the last of those bonds in full. Marked-to-market however, the country was ahead on the trade from day one, although it did require patience and discipline over two decades to fully materialize. The deal obviously did not solve every problem the country faced, and many critical issues remained for the U.S. to resolve going forward – some of them nearly life threatening. But that 1803 decision unarguably set the country on a binding and aligned positive trajectory as it exited an era of division and instability. Good American leadership today should look to this lesson, recognizing opportunity and chartering course in a similar manner.

“It is the case of a guardian, investing the money of his ward in purchasing an important adjacent territory; & saying to him when of age, I did this for your good.”

Thomas Jefferson, advocating for ratification of the Louisiana purchase in a letter to Senator John Breckinridge of Kentucky dated August 12, 1803

On the opposite side of the transaction, France approached the deal as a motivated seller in desperate hurry. In need of fast cash to re-capitalize its own treasury with war in Europe looming on the horizon, it immediately turned around and cashed out the par bonds it had received from the U.S. at less than 87 cents on the dollar. That high time preference decision was a good harbinger for its results that would follow.

Soon after closing on the sale in 1803, the Napoleonic Wars broke out and spanned the European continent for the next twelve years. While France climbed fast and achieved great heights at intermediate peaks as it nearly conquered the European Continent along the way, it ultimately found failure. In 1815, Napoleon met his final loss at the Battle of Waterloo and was sentenced to his final exile on the remote island of St. Helena. By the time the U.S. had finished paying off its debt on the deal in 1823, Napoleon had already passed away two years prior.

The arrival of today’s debt problem was foreseeable and would not fit the colloquial definition of a “black swan” surprise. For several decades the looming debt issue has garnered a moderate level of background attention, yet was always brushed aside by consensus opinion and kicked down the road by policymakers. Costly missteps in the post-9/11 era pushed the progression of the disease into critical territory: history will look back on two foreign wars and a massive public bailout to backstop the monetary crisis of 2008 as the crossing of the Rubicon. Yet even after these events, most still chose the comfort of denial in the mellow aftermath of the 2010s. It was not until the unparalleled policy response in the wake of panic during the COVID-19 pandemic that a catalyst pushed the diagnosis into terminal status.

While the Louisiana Purchase demonstrated a prudent use of borrowing by one American generation for a positive long-term result that it could hand down to future generations, the modern U.S. has shifted to the opposite end of the spectrum. The debt burden it has amassed for future generations in recent decades has delivered seemingly little to show for itself. Yet it was not that long ago that America could still claim to have fit that prior mold of leaving future generations with something better off than they had found it. At the current boundary of today’s living memory, the country exited the Great Depression and World War II at record levels of indebtedness, yet still managed several good borrowing decisions in the immediate aftermath. For example, the Highway Act of 1956 funded the construction of the Interstate system that still services a dominant share of the physical footprint of the U.S. economy. Over generations, the economic benefits delivered by that project covered its debt many multiples over.

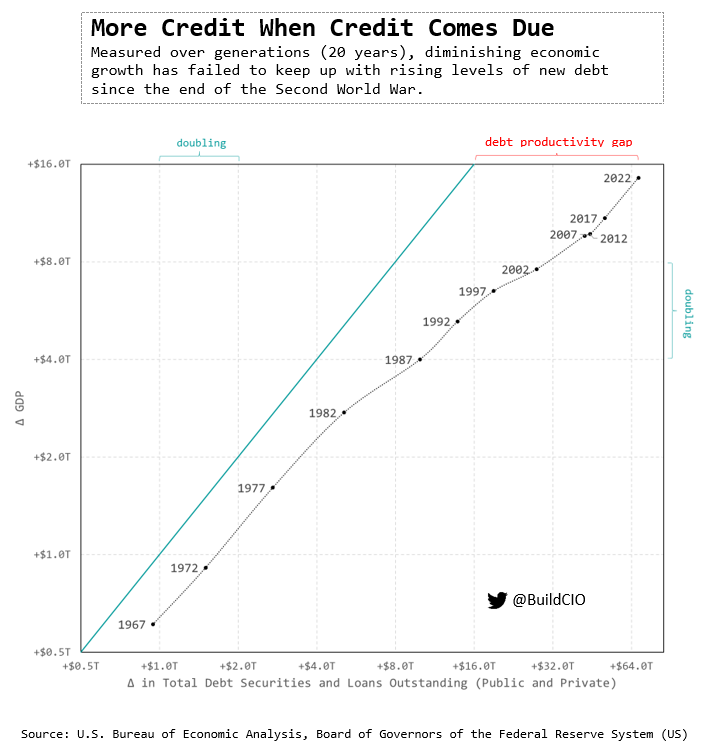

But after years of post-war growth and financial repression brought the debt burden back to maintainable levels by the 1970s, discipline began to wane. The U.S. broke its last remaining vestige to sound money in 1971 with the suspension of the convertibility of the U.S. dollar to gold in international foreign exchange markets, beginning an era of serial reliance on increasingly greater volumes of new debt to meet the basic objective of maintaining stable economic growth. Gradually, the country came to view debt solely as a tool to preserve and extend its existing economic model, rather than prudent practice and only capitalizing on its use once great opportunities presented themselves. The economic productivity of new credit progressively fell. As debt piled up, its output failed to keep up.

From the rear-view mirror, the debt-binge from the fiscal stimulus in the wake of the COVID-19 outbreak represents the problem’s current apex – at least for now. Amplified by the coordination of ultra-accommodative monetary policy, public officials expanded the total U.S. Treasury debt held by the public by 39% in a scorching three-year burst -- from $17.7 trillion in first quarter 2020 to $24.7 trillion in the first quarter of 2023.

It is hard to see where any long-term economic benefit will accrue from the debt incurred in this compressed time frame. The debt-funded spending did help directly staff the healthcare system with resources to fight a pandemic, but it also had to extend far beyond that useful perimeter to broadly support an entire economy from potential collapse. Spending bills passed during this time frame provided record unemployment assistance to stop self-perpetuating layoffs in a jobs market in free fall; injected billions of dollars into airlines to prevent them from falling into bankruptcy; and funded a moratorium on mortgage foreclosures, student loans, and tenant evictions. History will not look kindly upon these decisions: there was no future growth or opportunity supported by the new debt. But many hasty decisions over prior decades forced the country’s hand, with “systemic risk” once again providing the self-fulfilling justification as it had at every critical step along the way.

America’s recent decisions around the use of debt look more akin to Napoleon’s rushed impulse to satisfy immediate needs rather than a thoughtful, well-timed commitment to a long-term investment for future benefit. It becomes hard to do otherwise after prior decisions leave a nation constrained to no other choice, as Napoleon and countless others have learned. Rather than taking on debt in the name of sacrificing whatever it takes to achieve a long-term objective as the Jeffersonian vision exemplified, modern central bankers now find themselves stuck in the repetition of piling up debt as they continue to throw “whatever it takes” at any problem that surfaces an immediate risk of system failure. As Napoleon found out, the odds do not portend things ending well following this path.

After successfully forming a new government with the ratification of its Constitution in 1788, the U.S. finally had leeway to shift attention onto its broader economic considerations. During this stage, two wings formed around the opposing ideologies of Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton. Zoom out, and the embodied force of ideas behind these two founders can be seen in the ebbs and flows of America’s history. These two individuals served in the preeminent roles in George Washington’s founding administration, Hamilton as the country’s first Secretary of the Treasury and Jefferson its first Secretary of State. These two often found themselves representing opposite sides on every critical issue facing the country's first administration to occupy the Executive Office, and today’s present crisis – and its opportunity – represents another major contest in the long-run struggle for balance between both sides in the dualism of these two founders.

The Hamiltonian perspective can be broadly characterized by its advocacy for consolidation and centralization; the Jeffersonian camp for its promotion of liberty, individual rights, and decentralization. In their time, the key economic platform issues supported by Hamiltonians included the consolidation of Revolutionary War debts from the states to the federal level, the establishment of a national bank, and opposition to key Jeffersonian policies including the Louisiana Purchase. Headline economic issues for the Jeffersonians included the country’s westward expansion embodied by the Louisiana Purchase, reducing the national debt, and opposition to the important Hamiltonian platform positions such as the national bank. They also opposed corruption and what they observed to be a new aristocracy developing in American society.

Hamilton’s national bank stood out as one of the most divisive political issues in this time. While the intellectual lineage of today’s Federal Reserve can be traced back to the first national bank, the scope and powers of the original institution were diminutive in comparison to today’s central bank. Hamilton’s bank was unique in comparison to its peers only in that it could operate branches across state lines and lend money to the U.S. government. It was not tasked with the litany of monetary and economic policy mandates instilled in today’s Federal Reserve, including the conduct of open market operations; regulating the private banking industry; holding excess reserves of its member banks; acting as lender of last resort; maintaining price stability; or maximizing sustainable employment in the American economy. But despite its much smaller scope than today’s institution, the Jeffersonians saw risk in the national bank’s centralized powers and fought against it aggressively.

Today’s central banking system represents the logical progression of Hamilton’s platform after the advancement of two centuries. But its transition into the modern colossus, and the debt problem it has enabled the country to walk itself into, might be difficult for its original supporters to comprehend. It is hard to imagine that anyone in a position of civic responsibility in the days of the early republic, having almost certainly read Thomas Paine’s Common Sense in 1776 and likely been in possession of some of it personally, supporting the foolish backstop the model has converted itself into, with debt piling upon debt to no economic purpose beyond its perpetual bailouts of a system in repetitive failure.

In their day, the Jeffersonians sought to foster an American economy they hoped would allow the country to maintain the values of liberty and individual rights that they believed were core to the American Revolution. History would soon show that mapping those solid ideological foundations onto reality would prove to be the point of weakness. Jefferson’s economic platform supporting this vision depended on droves of self-sustaining, small-scale, land-owning family farmers that would settle the United States at it expanded westward. While the premise seemed valid from the perspective of a life in the 18th century, progress and technology would quickly prove it a quaint and wishful daydream within the span of a couple of generations.

Despite the increased availability of land as American westward expansion continuously progressed, innovations within the agricultural sector over time would relentlessly pressure the viability of American small-scale farming. Inventions such as the mechanical reaper, threshing machine, seed drill, steel plow, and cotton gin would lower costs, reduce labor intensity, and increase output per acre. Inevitably, the gains to scale enabled by technology led to consolidation. Farms grew larger and required less labor. Population growth shifted towards urban centers, and rural America struggled to keep up. Jefferson’s ideal of an agrarian economy was thwarted, but its ideological aspirations were hardly defeated – only delayed.

Jefferson failed to recognize the long-term effect of technological advance and its integration into economic life. While a static approximation to this process would have held up reasonably well to reality over the lifespan of an individual in the 18th century, the exponentially compounding effects of technological innovation would be revealed over long stretches of time. By no later than the midpoint of the 19th century, it was clear that this invisible force had shattered Jefferson’s idealized vision.

But the failure of Jefferson’s idealized economy to materialize does not negate the core values underlying the vision itself, nor the truth in their form as an enduring imprint on the American experiment from its inception. The political break simply reflects the reality that the available technologies over this time were inconsistent with the Jeffersonian vision. The tailwinds of 19th century technologies and their adoption favored the Hamiltonian vision. With the key technologies of the 20th century increasingly integrated into American life and adopted into its economy, the winds are now blowing at the Jeffersonian's back.

While the American agricultural economy was going through its disruption, broad innovations in the industrial and transportation sectors would accelerate the volume and pace of commerce to new heights. Exponential improvements in manufacturing enabled a massive expansion of production volumes and a drastic reduction in the cost of goods. Innovations in the transportation sector -- including the railroad, steam engine, oil drilling, telegraph, and refrigeration -- rapidly expanded the addressable markets for these goods. The bounty of technology in this period delivered economic growth unparalleled to anything seen in all prior human history.

Structurally operating under a coin and precious metals currency regime, credit and money were the primary limiting factors holding back this ascending growth. During the formation stage of the new country in the 1790s, the United States adopted a monetary model structured on gold and silver weights and measures as base money reserve for its banking system similar to the European powers of the day. Gold would emerge as the dominant base money standard with its official adoption by the Bank of England in 1821. Bills and bank notes, as claims on those reserves, proliferated in circulation in the private sector to keep pace with demand and facilitate the transactions fueled by the tailwind of technological progress and the rapidly expanding economy.

This pull from technology-driven growth in the private economy would deliver advances in money and banking that are often easily overlooked innovations. The arrival of the bank check allowed for transactions to be conducted in decimalized amounts, enabling clearing and settlement via entries in accounting ledgers as opposed to physical settlement of base metal reserves. The telegraph pushed the process one step further by enabling these transactions to be transmitted in electronic rather than physical (paper) form. The movement of monetary transaction units across accounting ledgers, rather than the movement of notes or coins, increasingly grew to represent a dominant share of financial transactions. Physical money got left in its dust. The process of the forced abstraction of money by technology has been underway for over a century, and continues to this day.

Problems began to pop up as this process took hold and the dominant volume of monetary activity shifted from the physical domain into the abstract. Bank balance sheets expanded to keep pace with real economic growth and demand, but the proportion of the abstract claims (credit) outpaced the growth of the gold holdings they were written against. When the ratio of claims relative to the underlying asset they were written against (leverage) increased past the point of no return, market volatility and cyclical default waves were a frequent result. Instability hit the U.S. financial system frequently during this era, with significant panics logged in 1792, 1796, 1819, 1837, 1857, 1873, 1884, 1893, 1896, 1901, and 1907.

As a proposed solution to these frequent bouts with financial panic, the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 created the central banking system in the United States that continues to operate up to present day. Seeking stability through centralization, it carries on the Hamiltonian tradition laid out at the country’s onset. Monetary linkages to gold were progressively severed over the first half of the 20th century, and the dollar-based credit standard came to dominate over the course of its remainder. Now two decades into the 21stcentury, this centralized credit growth monetary model has logged no less than two major panics of its own in 2008 and 2020. Its push to perpetuate itself via bottomless debt-based financing has brought the country to the debt crisis it finds itself up against today. As today’s participants in the American monetary system seek stability in an era of structural breakdown, tracing the arc starting in the nation’s formative days may provide a hint at its progress from current day.

From a day-to-day perspective it is easy to fall prey to the assumption that technological growth is stagnant. It blindsided Jefferson and played the fool to the entirety of his economic platform. But history has its tendency to show a fool to those who fail to heed technology’s impact. Those extrapolating continuity in the 20th century’s credit-based model risk making the same mistake. The historic losses and turmoil in sovereign bond markets, pop-up crises in banking and systemically important financial institutions, and the loss of purchasing power of credit-backed currencies observed in the post-COVID world suggest the error term is already blowing out.

“And I sincerely believe with you, that banking establishments are more dangerous than standing armies; & that the principle of spending money to be paid by posterity, under the name of funding, is but swindling futurity on a large scale.”

Thomas Jefferson in a letter to John Taylor during his retirement dated May 28, 1816

Just as the terminal decline of the credit-based monetary system inherited from the Hamiltonian tradition revealed itself in the global financial crisis in 2008, a peer was born representing its Jeffersonian antithesis. Whereas the new technologies of the 19th century enabled a wave towards the Hamiltonian identity in American society over the following century, clues that the technologies of the 20th century lean towards a Jeffersonian turn already hide in plain sight. Bitcoin is the zero-to-one, unique discovery of a trustless public monetary ledger. It is the natural outcome of the compounding of the 20th century’s key technological innovations in computing, semiconductors, networking, telecommunications, and cryptography.

History suggests it is common for societies to go through a period of struggle to comprehend a new technology in the interim between its arrival and its ultimate full adoption into daily life. Grasping the unfamiliar for the first time is almost always a challenge. Drawing on analogies with other technologies that are already familiar can help bridge the knowledge gap. For many, Bitcoin’s comparison to gold has been a helpful and popular analogy for developing an understanding of the unknown. Gold’s role in the financial system, however, has been pushed to a back seat with the ascendance of the credit-based model over the past few generations. The last holdouts advocating for a return to a sound money standard -- represented in a loosely organized group maintained in the proverbial “goldbug” caricature -- have held the line over many long decades while facing continuous headwinds. Today, this multi-generational trend leaves the public with only a small subset primed with an awareness to readily understand this new technology and the turning it represents. This may at least partially help explain why Bitcoin’s adoption appears difficult to see from the perspective of our day-to-day lived experience. Its exponential adoption is the measurable signal revealed through careful and thoughtful inspection over extended periods, though easily drowned out by the noise and volatility that come with a major disruptive transition.

Like gold, Bitcoin is a bearer asset that does not itself represent the liability of any third party: its value exists through its own existence and self-reference. As monies, both Bitcoin and gold can be transferred from one party to another for final settlement without the need for an intermediary. The fading, green Federal Reserve notes occupying Americans’ wallets and purses represent the current system’s version of this paradigm. However as a precious metal, gold by itself does not possess the properties of a ledger money: it requires the establishment of weights and measures enforced by a third party, and a mint to enforce these standards, to work as a money that counterparties can agree on in economic transactions.

Unlike gold, Bitcoin maps to the abstract space of information, rather than gold’s footprint in the physical. As a fully native ledger money, it internally balances and reconciles by its own design, absolving the need for third parties to enforce weights and measures. Like most transactions in the incumbent credit-based monetary framework, transactions representing change of ownership of units on the Bitcoin ledger take place fully electronically. In contrast to credit-based money however, Bitcoin’s internal ledger has no internal concept of leverage. Debits and credits, or the conceptual T-table entries of double entry accounting, are absent. And unlike copycats masquerading as step-wise progress on Bitcoin’s technological innovation, Bitcoin is the only public ledger money that does not require its participants to trust any external third party.

There’s a lot to grasp in that brief comparison. American society is only just beginning to understand the implications and complexities that a money with Bitcoin’s feature set brings to the table. Comprehension during a volatile transition away from an existing system going through terminal instability makes the task even more challenging. But market-observable signals of its adoption, such as its exchange rate and private fixed capital investment in the network, provide evidence in plain sight that it is outcompeting its alternatives. And as a finite and trustless ledger money asset, Bitcoin’s nascent but accelerating adoption as collateral may offer some hopeful stability as a tool to secure credit claims during the transitional unwind.

In what should come without surprise to readers who have made it this far, the U.S. dollar and its original sound money relationship with base metals bridges back to the struggle between Hamilton and Jefferson core to America’s foundation. The Coinage Act of 1792, enacted in George Washington’s first administration, laid the legislative foundation for money in the United States. It established the U.S. dollar as the country’s official currency, created the U.S. Mint, and specified weights and measures in gold and silver as base money. It specified that each coin possess an image emblematic of LIBERTY alongside the word itself, as well as the year of its coinage. While both Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson were members of this formative first cabinet of the United States that drafted its monetary framework, its beyond history’s reasonable doubt as to whose pen drafted those lines that still lives on in the design and inscription of the coinage produced by its Mint up to the present day.

As America seeks a path into its future out from its current crossroads, it carries with it the torch of liberty that defines its unrivaled spirit, identity, and sense of purpose that have been tied with the great experiment since it set forth on its Revolution nearly 250 years ago. Bitcoin as a technology represents the new, while coincidentally connecting America with its own monetary past. At the core, it represents the latest turn towards balance in the contradictions of its own personality that have been a feature since its very foundation. For a nation in transition and its participants looking for a brighter future, a great shift is already underway. Bitcoin recognizes no aristocracy. It tolerates no corruption. It advances liberty and champions individual freedom. The swell of opportunity of an American renewal is forming, and a new Jeffersonian awakening is at hand. For those desperate for its original promise to be carried forward, Bitcoin offers the hope of America’s best ideals.